Refugee Super Stars : On helping others and helping ourselves

By Lauren Klarfeld

Edited and Translated in Spanish by Leticia Municio Pardo here.

Published May 2017, Light House Relief Blog

Edited and Translated in Spanish by Leticia Municio Pardo here.

Published May 2017, Light House Relief Blog

“How… to… volunteer… in… refugee… camps” I typed in google that night, wondering if I had with it takes.

The refugee crisis resonated deeply with me when I heard it was about people who had lost their homes after having to flee theirs for economic or political reasons. In a way, I felt I had lived the same, at eighteen, when I came out to my parents, they didn’t accept it, and ultimately I had to choose between surviving a lie or living my life, staying in a place that didn’t accept me — or leave and look for refuge in a place that did. Since then my home had been in many places, but no so much in my heart....

By the beginning of April 2017, I booked my flight and headed out for a month to the small fisherman’s village of Skala Sikamineas and joined Lighthouse Relief. The NGO’s main activities consisted of cleaning the coast, keeping night watch over the waters, and being there for the refugee “landings”.

The refugee crisis resonated deeply with me when I heard it was about people who had lost their homes after having to flee theirs for economic or political reasons. In a way, I felt I had lived the same, at eighteen, when I came out to my parents, they didn’t accept it, and ultimately I had to choose between surviving a lie or living my life, staying in a place that didn’t accept me — or leave and look for refuge in a place that did. Since then my home had been in many places, but no so much in my heart....

By the beginning of April 2017, I booked my flight and headed out for a month to the small fisherman’s village of Skala Sikamineas and joined Lighthouse Relief. The NGO’s main activities consisted of cleaning the coast, keeping night watch over the waters, and being there for the refugee “landings”.

When the first “landings” of refugees arrived in the area in 2015, there were still no NGO’s set up on the island. I learned that back then it was up to the local fishermen to fish out the men, woman and children from the waters. Meanwhile it was Tula and her staff at the Goji’s Café that came in aid as the first waves of refugees began to wash up at the steps of her little oceanfront café.

As the media made progressive use of the label “refugee crisis”, the little-known fishing village received increasingly more coverage; locals recounted how the region witnessed an incoming tide of humanitarian workers… all the while flooding with writers, journalists, photographers and documentarists. Villagers grew more and more accustomed to the presence of foreigners, against the backdrop of prices silently rising and new rooms opening-up for rent.

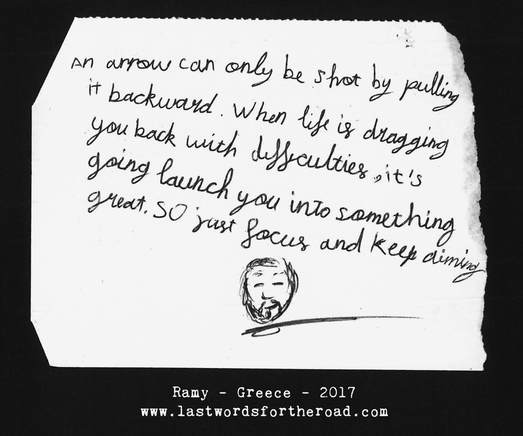

A few days into my volunteering I sat down for a coffee at Goji’s Café and befriended a Syrian guy named Ramy. Ramy had apparently crossed about a year ago, and after some time in the camps, managed to establish himself in Skala where he volunteered as a translator for the newly arrived refugees. He was still waiting on the answer for his asylum status.

I could trace a kind and cartoon-like smile through his heavy beard, and he had a bulky laugh that made his whole body shake as he chuckled. I liked that about him. But it also contrasted greatly with the shades of darkness in his eyes

When Ramy and I weren’t playing chess or smoking cigarettes together, we would talk about his life back in Syria. About his job and his latest 3D animations, about silly memes we’d seen on the internet and about our families and ex-girlfriends. And sometimes, we would talk about how he got to Europe.

That’s when he avoided eye contact the most, as the story that he lived was a grim one; of his boat capsizing in the middle of the night and having to swim for eight hours until he reached the beach with a torn life jacket in one arm and the body of a lifeless child in another… But if Ramy’s eyes were evasive, it wasn’t because of the content nor the nature of his story. I felt him avoiding my eyes because it wasn’t the first nor the second time that he shared his story and that he faced the questions that ensued.

When hearing these stories of survival, I realised many had already received coverage. Film festivals, newspapers, magazines, documentaries, photography competitions and even blog posts had all tried to wake the world up to what was happening.

However, in the meantime, newspapers got sold, photographers won pictures of the year awards, and influencers received more likes than ever before. It was hard to reconcile with the idea that when the journalists travelled to the refugee camps, they came to study it; they came wanting to live something that was worth writing about. Refugees were not people, but concepts; and once the interview was over, they came back with a story, but the refugees never got much in return.

In this sense, Ramy was a story before he was a person and it sold like a tabloid.

But when the journalists left, the volunteers stayed.

On my last night there, one of the walkie talkies that was vigilantly placed on one of the café’s tables started to blare voices : “Korakas to Camp — Korakas to Camp –Refugee dinghy spotted — 42 people coming your way in 10 minutes — Over”. A dingy with forty-two people in it had been intercepted while floating around with a broken engine. It was 2am, and the rescue boats from Proactiva Open Arms were towing it to land. Automatically we all took positions and waited for the boat to appear out of the darkness. In a matter of minutes, we were handing out water and emergency blankets to the recently arrived, while some journalists who were present were already snapping pictures. The flashes reflected off of the aluminized emergency blankets — and the discomfort reflected in their eyes. Quickly the group was moved to the Stage 2, where we were told to wait with them until the police came to transfer them to Moria Camp, the ‘official’ camp for refugees. We arrived, handed out food, and offered first aid care to a grandmother whose feet were tapped together in an effort to protect them from the water that had already consumed them, and we waited, and waited…

By then it was 4am already, and while some dozed off exhausted from the journey, others were playing football with the volunteers, a sport that everyone knew how to play, despite the language differences and that needed no words. The only sounds that broke the silence of the night, were those of laughter, voices and lighters lighting cigarette after cigarette until dawn. And it felt as if the real work happened here, where refugees felt a little less like refugees, and people were just being people.

As the media made progressive use of the label “refugee crisis”, the little-known fishing village received increasingly more coverage; locals recounted how the region witnessed an incoming tide of humanitarian workers… all the while flooding with writers, journalists, photographers and documentarists. Villagers grew more and more accustomed to the presence of foreigners, against the backdrop of prices silently rising and new rooms opening-up for rent.

A few days into my volunteering I sat down for a coffee at Goji’s Café and befriended a Syrian guy named Ramy. Ramy had apparently crossed about a year ago, and after some time in the camps, managed to establish himself in Skala where he volunteered as a translator for the newly arrived refugees. He was still waiting on the answer for his asylum status.

I could trace a kind and cartoon-like smile through his heavy beard, and he had a bulky laugh that made his whole body shake as he chuckled. I liked that about him. But it also contrasted greatly with the shades of darkness in his eyes

When Ramy and I weren’t playing chess or smoking cigarettes together, we would talk about his life back in Syria. About his job and his latest 3D animations, about silly memes we’d seen on the internet and about our families and ex-girlfriends. And sometimes, we would talk about how he got to Europe.

That’s when he avoided eye contact the most, as the story that he lived was a grim one; of his boat capsizing in the middle of the night and having to swim for eight hours until he reached the beach with a torn life jacket in one arm and the body of a lifeless child in another… But if Ramy’s eyes were evasive, it wasn’t because of the content nor the nature of his story. I felt him avoiding my eyes because it wasn’t the first nor the second time that he shared his story and that he faced the questions that ensued.

When hearing these stories of survival, I realised many had already received coverage. Film festivals, newspapers, magazines, documentaries, photography competitions and even blog posts had all tried to wake the world up to what was happening.

However, in the meantime, newspapers got sold, photographers won pictures of the year awards, and influencers received more likes than ever before. It was hard to reconcile with the idea that when the journalists travelled to the refugee camps, they came to study it; they came wanting to live something that was worth writing about. Refugees were not people, but concepts; and once the interview was over, they came back with a story, but the refugees never got much in return.

In this sense, Ramy was a story before he was a person and it sold like a tabloid.

But when the journalists left, the volunteers stayed.

On my last night there, one of the walkie talkies that was vigilantly placed on one of the café’s tables started to blare voices : “Korakas to Camp — Korakas to Camp –Refugee dinghy spotted — 42 people coming your way in 10 minutes — Over”. A dingy with forty-two people in it had been intercepted while floating around with a broken engine. It was 2am, and the rescue boats from Proactiva Open Arms were towing it to land. Automatically we all took positions and waited for the boat to appear out of the darkness. In a matter of minutes, we were handing out water and emergency blankets to the recently arrived, while some journalists who were present were already snapping pictures. The flashes reflected off of the aluminized emergency blankets — and the discomfort reflected in their eyes. Quickly the group was moved to the Stage 2, where we were told to wait with them until the police came to transfer them to Moria Camp, the ‘official’ camp for refugees. We arrived, handed out food, and offered first aid care to a grandmother whose feet were tapped together in an effort to protect them from the water that had already consumed them, and we waited, and waited…

By then it was 4am already, and while some dozed off exhausted from the journey, others were playing football with the volunteers, a sport that everyone knew how to play, despite the language differences and that needed no words. The only sounds that broke the silence of the night, were those of laughter, voices and lighters lighting cigarette after cigarette until dawn. And it felt as if the real work happened here, where refugees felt a little less like refugees, and people were just being people.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed